Wage Rights, Social Security and Academic Institutions: Will the Bills for Unorganised Sector Workers help?[1]

-Yogesh Snehi

Abstract

_____________________________________________________________________

In 2004-2005, a concerted campaign was organized by Initiatives for Democratic Rights (IFDR)[2],

Socio-economic Findings of the Survey

The idea behind conducting a survey on the mess/canteen workers of

The survey primarily focussed on the socio-economic conditions of the mess/canteen workers employed in the hostels of

The survey primarily highlighted the socio-economic conditions of the workers.[6] Virtually every hostel worker (in both boys’ and girls’ hostels) interviewed was a migrant labourer, all of them being males. Most of them had left their families as teenagers, coming alone or with their relatives to

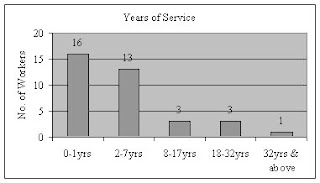

Land can ensure a minimum social security for the rural population. However, this depends on how much land is owned. The survey found that almost two-third of the workers were from families that were either landless or owned five or less kanals of land, which is barely sufficient even for subsistence farming. Most of the workers interviewed were between 19 to 25 years of age. Almost all of them joined the mess/canteen services between the age of 14 and 25. Two of them were below the age of 14 when they joined. While a majority of them had been working at this job for less than one year, a few had held the same job for as long as 42 years.

A worker’s age and the number of years of service should be an important factor in determining his wages and service entitlements. However, even those workers who had been working in the hostels for many years were not getting any better wages or entitlements than young boys who have been working for less than one year. To add to it lack of education was another source of deprivation. Although education itself does not necessarily guarantee job security but as Amartya Sen argues, it does enhance the capabilities to choose. However, we found that six workers among thirty-six were illiterate. While most of the mess/canteen workers had studied at least up to eighth standard, one had completed 10+2.

Caste discrimination can be one of the reasons why even educated people are forced to work under bad conditions at low-paying jobs. According to the survey, as many as one third to one half of these mess/canteen workers belonged to the Scheduled Castes or Other Backward Castes. This higher than expected ratio (given the lower percentage of these castes in the total population), indicates the continuing prevalence of caste discrimination in which the dalit population does not have equal opportunities to higher paying jobs.

Wages and Working Conditions

The University does not consider either the contractors or the workers as its regular employees. Therefore, the latter are deprived of the benefits to which the regular employees are entitled.[7] Most of the mess and canteen workers work for more than 12 hours each day, and all of them work for 7 days per week. None of them gets overtime pay for the extra hours worked.

Only three of the thirty-six workers interviewed got more than Rs.1500 pm. One worker merely received Rs.600 pm, and another got only Rs.1100 pm even though he had been working at the hostel for the past 42 years. Thus, there is an inequity in the correlation between wages, hours of work and years of service. Three workers who were getting the maximum salary were basically cooks, who worked fewer hours each day than the others. With such low wages and busy schedules, most of the workers could visit their native place just twice or thrice in a year. In most cases, the workers paid for whatever medicines they needed from time to time. Out of thirty-six workers just ten of them said that they received some medical benefits.

The conditions in which the workers live make a mockery of the welfarism guaranteed by the socialist notions of our Constitution. While some workers were sharing tiny sleeping rooms with 2 or 3 fellow workers, most used small rooms shared by

Most of the workers were not satisfied with their working conditions. They felt bound by necessity since there are fewer opportunities of alternate employment available to them outside the university premises. Besides this, they often face verbal abuses. Two of them narrated incidents of their physical abuse by the hostel students. Seventeen workers also reported incidence of stress due to overwork. These were mainly canteen workers who work for more than eleven hours in a day. Although there are some facilities to accommodate the families of contractors, nothing is available for the workers’ families.

Question of Rights

Labour laws came into existence after decades of struggles over working conditions, hours of work and wage entitlements, etc. These reforms came into being with the parallel transformation in the 19th century vis-à-vis the nature of the State from feudalism to welfarism. Indian Constitution spells out the welfare character of the state based on the principles of social justice. Labour laws also extend the provisions for service and legal entitlements of labourers.

Any labourer/worker, whether on contract or regular basis, is entitled for certain basic rights. Firstly, the Minimum Wages Act of 1948 specifies the statutory minimum wages payable to a worker. The appropriate governments from time to time revise the rates under this act, keeping in mind the growing cost of living. The Labour Department of Chandigarh has fixed minimum wages as follows;

| Category | 1 April- | 1 April- | ||

| pm (Rs.) | per-day (Rs.) | pm (Rs.) | per-day (Rs.) | |

| Unskilled | 2741.50 | 105.35 | 3211.50 | 123.20 |

| Semiskilled (2) | 2891.50 | 111.15 | 3361.50 | 129.00 |

| Semiskilled (1) | 2991.50 | 114.95 | 3461.50 | 132.80 |

| Skilled (2) | 3191.50 | 122.65 | 3661.50 | 140.50 |

| Skilled (1) | 3416.50 | 131.35 | 3886.50 | 149.20 |

Source: Labour Bureau,

Besides this, if a worker covered under these provisions and working in canteens, etc. is not provided any provision for food and accommodation, an extra payment of Rs.333.31 pm, increased to Rs.392.00 pm in April 2006, should be provided.

Secondly, the Factories Act of 1948 says that every worker shall be entitled to all the privileges and benefits applicable to the workers in a factory. These provisions relate to the hours of work; which includes (i) weekly holiday on the first day of the week (ii) work for not more than 48 hrs a week and not more than 9 hrs a day (iii) overtime for work more than 9 hrs on any day or more than 48 hrs in a week at the rate twice the ordinary rate of wages (iv) maintenance of a register of workers; health and safety of workers, food and accommodation, annual leave with wages in the subsequent Calendar year, if he has worked for 240 days or more in a Calendar year i.e. one leave for 20 days of actual working, in the case of an adult and one leave for 15 days actual working, in the case of a child.

Thirdly, the Employees Provident Fund and Misc. Provisions Act, 1952 says that a prescribed contribution has to be made by the principal employer in respect of contractor's employees. Fourthly, the

In addition to this, the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970 has made it obligatory for the contractor employing contract labour to provide and maintain sufficient supply of wholesome drinking water and reasonable number of latrines, urinals, washing facilities, etc. Where the contractor does not provide such facilities and amenities, the responsibility shifts to the principal employer. Mess/canteens are provided under the statute i.e. The University Act. In the view of G B Pant University Vs the State of Uttar Pradesh, the University (in this case the Panjab University) is the principal employer of the workers employed in the hostels of the institution.

The survey revealed serious violations of the rights of mess/canteen workers. Not even a single provision for workers pertaining to the maintenance of registers, minimum wages, hours of work, overtime, health and accommodation, leave entitlements, provident fund and employees' state insurance have been implemented in the Panjab University campus.

Workers receive wages far below the minimum wages. One of the worker interviewed received wages as low as Rs.600 pm. Most of the workers work for more than 9 hrs a day regularly. These working hours extend to 12 hrs for some canteen workers. They do not get any extra benefits for overtime. Besides this no worker gets a holiday in a week. Provision of health and accommodation is also inadequate. In some hostels they sleep on the dining tables. They are not provided annual leave with wages even though every worker works for more than 240 days in a year. When a worker goes on leave he is deprived of his wages even if he uses the leave to which he is entitled. The University (principal employer) does not maintain Provident Fund and Employees' State Insurance.

A Judgement of Supreme Court of India in the case of

Admittedly, Cafeteria employees need succour – would they continue to remain half fed and half clad as long as they live– is this the society that we feel proud of? Is this the guarantee provided by the founding fathers of our Constitution or is this the concept of socialism which they conceived? None of the answers can possibly be in the affirmative. The situation is rather awesome and deplorable – the University by compulsion directs students to be residents of hostel with a definite ban on having food from outside agencies excepting under special circumstances and the provider of food, namely, the staff of the Cafeteria ought not to be treated as an employee of the University…[8]

The University, through the Dean Students’ Welfare (DSW) enters into a procedure of appointment of contractors for one year (renewed every year) on the basis of an ‘Agreement Bond’, which mentions the terms and conditions of the contract. Here the University acts in the capacity of a ‘principal employer’. The Agreement Bond regulates the functioning of mess/canteens. It not only specifies provisions of basic furniture, fuel, cylinders, cooking utensils, etc., which are provided by the University but also emphasizes the guidelines pertaining to the rights of workers. Also the ration to run these mess/canteens has to be essentially purchased from the University. [9] One the one hand it lays down the standard of food, appoints a dietician to check the quality of food and fixes the rates of diets, while on the other hand it instructs the contractors ‘to observe and follow general labour laws, employment acts and wage rules’ [Agreement Bond 2004: 2]. The University also undertakes the collection of mess/canteen dues from the students and pays it back to the contractor after deductions.

In a way the University acts as the ‘principal agency responsible for the employment and welfare of workers’, and should comply with the legal provisions. Its role becomes more interesting when it provides Rs.700 pm as a salary subsidy to the contractor as if he is an employee of the University.

The University regulates the employment of more than 400 workers working in various mess/canteen of twelve hostels. These workers start working with effect from 15th of July, when the session starts, till the month of May, for a span of around 10 months i.e. more than 300 days. Usually the worker continues with the work in the next session also as the contracts are ritually renewed every year. Also the contractor continues to work in the same hostel for years together until there is a serious breach of terms. The contractor of Mess-I of Hostel-6 had been working there for more than 20 yrs. Thus the contractors continue to work in the University system year after year and are sometimes mutually transferred but very rarely removed.

The University has also fixed rules and regulations for the students/residents regarding their association with mess/canteens.[10] It says that a ‘hostel has facilities for lunch and dinner as well as canteen services and a resident shall have meals in the hostel mess/canteen only (Rule 37-a); ordinarily residents will take food in the hostels and the residents are required to take at least 15 diets per month, failing which a minimum charge of 15 diets is to be paid by them (10 diets to be paid to the contractor and 5 diets to the Mess Development Fund) in the mess where they are residing (Rule 37-b); each resident will contribute charges of two ordinary diets per month (along with the mess bill) one towards food subsidy and one towards Mess Development Fund (Rule 37-f); for the meals missed by a resident, without the prior intimation, a charge of Rs.3 per meal will be imposed. It will be obligatory on the part of the residents to inform the Contractor/Cooperative Mess Secretary before hand if they want to miss a meal so as to avoid the wastage and loss. A register for this purpose will be available with the contractor wherein the residents should enter the information about missing the meals. A resident who is absent without leave from the Warden may miss meals for not more than seven days in a month (Rule 37-h).’ Further the fee structure of the hostel rulebook imposes (under item 46 B) contributions towards a Mess/Canteen Servants Welfare Fund @ Rs.10 pm and Medical Aid of Mess/Canteen servants @ Rs.40 pa on the students.

Thus mess/canteen services do not seem to be a mere welfare activity but is an essential requirement where sizeable number of employees work. These services are provided on a regular basis and the university cannot do away with them. Further, the University has total control in the matter of running and maintenance of the mess/canteens. The contractors have only been acting for and on the behalf of the University as its agents to provide the said services. The contractors engaged from time to time are in reality the agents of the University and are only ‘a veil’ between the University and the canteen workers. Hence the workers are in fact the employees of the University.

One of the most significant finding of the survey conducted by IFDR was either absence or low awareness of mess/canteen workers about the legal entitlements that are due to them. They are unaware that their working conditions are illegal. Some others do not have any faith in the law. This is despite the fact that many among them have completed their education up to at least eighth standard.

Campaign and Reaction of the Authorities

Low awareness amongst the workers gave an impetus to the efforts for development of a methodology to engage these unorganised workers with the issues of wage rights. A poster in Hindi which highlighted the basic wage entitlement of workers was prepared by the members of IFDR.[11] Meetings with workers were organised in the different hostels to make the workers aware of their wage rights. Efforts were also made to organise them so that they can meet regularly and discuss issues of minimum wages, living conditions, dealing with recurrent verbal and physical abuses from the students and evolving a possibility to create a pressure group which could evolve in the form of a registered body to press the authorities for their statutory rights. Significantly, when the president of fourth class union was contacted to take up the issue of mess/canteen workers, he expressed his inability to engage with them.

The result of this engagement was dramatic. The workers started turning up in significant numbers at the joint meetings which were preferably held in the evenings in the university campus. One such meeting was organised by the workers themselves at eleven in the night under the leadership of a canteen accountant of Hostel-2. More than three hundred workers from different hostels turned up at this meeting. It was disorganised and ill planned and the sheer number and the time sent the alarm bells ringing. The workers engaged in sloganeering and almost immediately the University security turned up and scattered them. Their leader was called up and given a warning. These developments lead to an almost immediate beginning of repression on the workers by the University authorities, especially hostel wardens.

In another development a worker of Hostel-4 was beaten up by some students on the charges of theft.[12] This agitated the workers and they decided to go on a strike. The workers of other hostels were gradually informed and a call for total strike was given. Though unorganised, these workers met at the law ground of the University.[13] The warden used this case as a justification to curb the activities of workers. Instead of trying the students who had beaten up the worker, the warden took to their sides. The leader of Haryana Students Association demanded that the workers be fined for striking. The warden criminalised the ‘community of workers’. All this happened in the common room of Hostel-4 in presence of another warden and a dietician. Since the charge of theft could not be proven the warden expelled the worker on the charges of selling cigarette and fined the contractor with Rs.5000.[14] The workers of other hostels were threatened with expulsion. Slowly the meetings came to a standstill.

In the meantime the authorities sent a circular that a three-day training workshop for the workers shall be organised in association with Ambedkar Institute of Hotel Management,

The reaction of the student community and the attitude of authorities raise many questions about the general insensitivity on the question of wage rights which prevails in our society. IFDR decided to work on this issue with a fresh perspective to bring the student community closer to the issues of the oppressed. Besides this, a parallel campaign to sensitize this issue in the University was launched.[15] The issue was also raised at the senate meeting held on

Meanwhile, IFDR undertook a poster campaign and brought forth issues like democratic/legal rights and welfare of workers, accountability, constitutional and statutory rights and respect for the labour laws.[17] These posters were put around the University campus and IFDR tried to sensitise the student community on the question of wage rights. But such issues are never taken up by student bodies engaged in election politics. An effort was made to make an enquiry into the utilisation of two funds (Mess/Canteen Servants Welfare Fund and Medical Aid of Mess/Canteen Servants) maintained for the welfare of workers through ‘Right to Information’. DSW office provided IFDR with a false statement on Income and Expenditure for these funds. IFDR questioned these details but repeated applications to the DSW and the appellate authority have fallen to deaf ears.

Indian Scenario

Indian scenario is not different from the case study of mess/canteen workers of

There are numerous organisations in

Pointing towards the efficacy of the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, a ‘Report on the Working of Minimum Wages Act, 1948’ says that in a developing economy like India where about 90 percent of the workers work in the informal sector without having collective bargaining power, wages couldn’t be left to be determined entirely by the interplay of market forces and intervention on the part of the government becomes imminent. It says that it is with this objective of supposedly protecting the vulnerable and the less privileged strata of the society from exploitation by the capitalist class that government of

Another ‘Report on Evaluation Studies on Implementation of the Minimum Wages Act, 1948’ says that the Minimum Wages Act, 1948 aims at preventing exploitation through the payment of un-duly low wages in such employments where ‘sweated' conditions exist and the workers are vulnerable due to lack of organisation; illiteracy; ignorance and poverty etc. The Act, therefore, empowers the appropriate government for fixing the statutory rates of minimum wages and to revise the same at intervals not exceeding 5 years for the Scheduled employments.’ However, the report admits that the fixation of the statutory minimum wages in itself does not ensure that it is paid to the target workers. It requires effective enforcement on the part of appropriate authorities.[21]

In such a situation there is a need for an affective framework which can cater to the social security needs vis-à-vis minimum wages, education, health, insurance and housing needs of these people. The existence of present framework of laws like The Minimum Wages Act, The Factories Act, The Employees Provident Fund and Misc. Provisions Act, The Employees State Insurance Act and The Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act have hardly been helpful as Labour Bureaus and inspectors make a mockery of these provisions by being silent and passive. Our own experience has shown that repeated letters and appeals to the labour department fall to deaf ears.

The Unorganized Sector Workers Bill

Unlike the organized sector, there is no fixed employment relationship in the unorganized sector. The peculiar nature of the unorganized sector of around thirty-nine crore workers is the changing employer - employee relationships and the existence of a hierarchy of relationships. The employment is contractual, most often on a sub-contract basis and is unregulated and thus the workers are unprotected. Thus, to ensure security of employment and protection of workers, it becomes imperative to regulate employment in the unorganized sector.[22] Though social security laws such as the ESI Act, EPF Act, Payment of Gratuity Act etc., have been extended to the unorganized sector, constraints in their application have been experienced due to lack of continuity of employment, the changing employer - employee relationship and total lack of records pertaining to the details of employment.[23] Further, there was a felt need that minimum level of social security particularly in the areas of health, maternity benefits, disability & old age benefits must be provided, if necessary through public assistance also.[24]

There has been a significant headway on the issues of unorganised worker in the recent past. The National Campaign Committee for Unorganised Sector Workers has been working in many ways to moot provisions for social security of workers in the unorganised sector. It is an umbrella group of various organisations working in this sector. A major initiative on this issue came from the Ministry of Labour which brought out the third draft of Unorganised Sector Workers (Regulation of Employment, Conditions of Service, Social Security and Welfare) Bill in November 2004 and was put forth for discussion. Besides this, Sushma Swaraj also introduced the Unorganised Labour and Agricultural Workers (Welfare) Bill in July 2005. In August 2005, the National Commission for Enterprises in Unorganised Sector (NCEUS)[25] brought out two draft bills for workers in unorganized sector; Unorganised Sector Workers Social Security Bill, 2005 and Unorganised Sector Workers (Conditions of Work and Livelihood Promotion) Bill, 2005. On

The Commission has proposed a ‘national minimum social security scheme’ for all unorganised workers, which shall include health benefits, insurance cover cum unemployment benefits for workers above poverty line (APL) and a pension of Rs.200 per month for aged workers living below poverty line (BPL). The scheme is proposed to be contributory in nature with workers employers and government contributing one rupee each per day towards the scheme. However workers living below poverty line will be exempted from their contribution which shall be paid by the central government on their behalf. The central and state governments in the ratio of 75:25 shall share the remaining government contribution.

Unorganised Sector Workers Social Security Bill 2005 will cover all workers in the unorganised sector with a monthly income of Rs.5, 000 and below. This will include self-employed workers (including small and marginal farmers), wage workers and home based workers. In addition, informal workers in the organised sector without any social security cover (such as Badli workers and casual workers) will also be covered. The number of workers eligible for this cover is estimated to be around 30 crores. There will be a national minimum social security cover comprising (a) health insurance, (b) maternity benefits, (c) life insurance and (d) old-age pension for all eligible workers.[26]

Unorganised Sector Workers (Conditions of Work and Livelihood Promotion) Bill, 2005 proposed by the Commission seeks to address the question of conditions of work for wage workers in the unorganised sector with a view to provide a basic minimum standard on hours of work, payment of minimum wages and adherence to Bonded Labour Abolition Act and Child Labour Prohibition & Regulation Act. It also recognises a set of minimum entitlement of the workers comprising (a) the right to organise (b) non discrimination in the payment of wages and conditions of work, (c) safety at the work place and (d) absence of sexual harassment.[27] In order to provide machinery for the resolution of disputes between wage workers and employers in the unorganised sector, the Draft Bill has proposed the creation of at least one Dispute Resolution Council in every district which would be constituted by the State Governments. Before adjudicating on a matter, the Dispute Resolution Council shall, in the first instance, try to arrive at a conciliated settlement of disputes. The Council will have the powers of a

How far can the Proposed Bills go?

Unorganised Sector Workers Social Security Bill, 2005 and Unorganised Sector Workers (Conditions of Work and Livelihood Promotion) Bill, 2005 propose a framework for devising a social security mechanism and the furtherance of livelihood and work conditions of the unorganised workers. These Bills seek to propel and extend social security coverage to all the states and all the groups of workers in the unorganised sector. The experience of existing labour laws, however, demonstrates that the mere existence of legal frameworks may render the laws redundant in the absence of an efficient arrangement for their implementation, with effective checks and balances.[29] The case study of mess/canteen workers of

The latest Bills on unorganised sector workers have brought out significant improvements over earlier drafts. The proposed National Social Security Scheme consists of old age pension, health insurance, maternity benefits, insurance to cover death and disability arising out of accidents to every registered worker. In addition to these schemes the respective governments may frame other schemes for provident fund, housing, educational needs of children of workers, skill up gradation, funeral assistance, marriage of daughters, etc. for the socio economic security of the unorganised sector workers. In order to make National Social Security Board effective, it shall include the representatives of national-level unions and voluntary associations of the unorganised sector workers. Besides this, every unorganised sector worker shall be issued a Unique Identification Social Security Number which shall be valid even in the case of migration of workers to other districts. All unorganised sector workers shall have the right to organise themselves for collective bargaining.

These provisions will have a bearing on the mess/canteen workers of

Unorganised Sector Workers (Conditions of Work and Livelihood Promotion) Bill, 2005 says that no employer shall employ an unorganized sector wage worker in contravention of the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976, Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986, The Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993 and Minimum Wages Act, 1948 but it excludes The Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970 from this clause. The Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act says that the places where the work is of perennial nature, the employer should employ regular workers. But the new bill may emerge as a contradiction with the existing provisions of labour laws. The workers entitled to regular wages may be classified as unorganised and the employer will conveniently try to do away with his statutory duties.[30]

Besides this, Hirway points out that the unorganised workers are a highly heterogeneous group of workers. They include workers employed in a wide range of economic activities, from street vendors and casual workers in a tea-shop to bidi workers, brick kiln workers, salt pan workers and sub-contracted and temporary workers of factories. The different economic activities in this sector are at different levels in terms of technology, productivity, wages and profits. The affordability and the paying capacity of employers as well as the needs of workers for social security will therefore be different in different activities. A uniform package will not be valid for the different categories of workers [Hirway 2005: 380].

How far can these Bills be successful in ensuring minimum wages to the unorganised sector workers remains in question? The existing framework of Labour Bureaus is highly problematic. By limiting its duty to fixing minimum wages, Wage Boards leave a vacuum as far as the implementation of these provisions is concerned. Labour Commissioners and Labour Courts continue to be biased. Even the institutions of higher learning do not perform their statutory duties. How effective will the new framework of State Advisory Committee be, remains a pertinent question? Minimum wages are a minimum security against poverty, hunger and deprivation and unless this is ensured provision of social security will merely be an eyewash. Therefore, any enactment on social security of the unorganised sector workers should first ensure the payment of statutory minimum wages to workers. Unlike Right to Information Act, 2005, the new Bills do not prescribe any punitive mechanism in the cases of non-adherence to the provisions of these Bills or other labour laws. There is an urgent need to break the nexus between employers and labour commissioners and penalising the authorities who work contrary to labour laws.

The Supreme Court Judgment in the case of G.B.Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Nainital vs The State of Uttar Pradesh and Others remains unequivocally significant on the question of wage rights and social security. “These are the questions which remain unanswered: ...The society shall have to prosper and this prosperity can come only in the event of there being a wider vision for total social good and benefit. It is not bestowing any favour to anybody but it is a mandatory obligation to see that the society thrives. The deprivation of the weaker section we had for long, but time has come to cry halt and it is for the law courts to rise up to the occasion and grant relief to a seeker of a just cause and just grievance. Economic justice is not a mere legal jargon but in the new millennium, it is the obligation for all to confer this legal justice to a seeker.”[31] In a critique to the third draft of The Unorganised Sector Workers Bill, 2004, the National Campaign Committee for Unorganized Sector Workers stated that any law for unorganized sector workers should not be merely welfare oriented but also provide for regulation of employment, minimum employment earnings guarantee and role for workers in the enforcement of the law and the scheme, including workers participation in the formulation of the scheme.[32] These new Bills for unorganized sector workers may provide a hope for mess/canteen workers of academic institutions like

References:

Chaitanya,

GoI (1998): Report on the Working of Minimum Wages Act, 1948, Labour Bureau, Government of

__ (2001): Report on Evaluation Studies on Implementation of the Minimum Wages Act, 1948 in Bidi Making Establishments in Madhya Pradesh, Labour Bureau, Government of

Hirway, Indira (2005): ‘Unorganised Sector Workers' Social Security Bill, 2005’, Economic and Political Weekly, February 4, pp.379-382.

Initiatives for Democratic Rights (2004): Who Serves us Food: A Report on the Rights of Mess/Canteen Workers of Panjab University, Initiatives for Democratic Rights,

National Campaign Committee for Unorganized Sector Worker (2005): The Unorganised Sector Workers Bill, 2004: A Critique, National Campaign Committee for Unorganized Sector Worker,

__ (2004):

__ (2005):

V. V. Giri National Labour Institute (2002): Proceedings of the National Seminar on Unorganised Sector Labour: Social Protection, Skill Development and Legislative Intervention held on

[1] Acknowledgements: This paper is based on a survey of mess/canteen workers of

[2] The issue was raised under the banner of Initiatives for Democratic Rights (IFDR), a group formed by students, academicians and other concerned citizens of

[3] IFDR is associated with Critique, a students’ discussion group at

[4] The members of IFDR prepared the questionnaire. It intended to collect personal information on age, age when the worker joined the mess/canteen services, native place, land owned, reasons for migration, and specific data on years of employment, hours of work, wages per month, hours of sleep, accommodation, provision of food and clothing, medical benefits, whether faced verbal or physical abuse, whether stressed or overworked, entitlements to increments, alternate source of income and knowledge about labour laws. Besides this, unstructured information on how often a worker visits home and whether he sends his wages back home was also included in the questionnaire.

[5] Each of the 12 hostels (seven Boys’ Hostels and five Girls’ Hostels) has two messes which serve two meals per day and one canteen which serves breakfast and snacks throughout the day. Each mess or canteen has one contractor, in addition to about a dozen workers, thus making a total of about 425 workers serving more than 5000 people each day. Thirty-six workers were randomly chosen for the survey from three Boys’ Hostels (Nos. 4, 5 and 6) and one Girls’ Hostel (No. 5) on the

[6] These findings were released in the form of a report Who Serves us Food: A Report on the Rights of Mess/Canteen Workers of Panjab University by Initiatives for Democratic Rights,

[7] In the latter part of the paper, we shall discuss how the workers were denied their basic wage rights despite the fact that the mess/canteens of

[8]

[9] As per the Agreement, certain items of the ration have to be necessarily purchased from the University (e.g. Brookbond Tea, Markfed cooking oil). The contractors complain that sometimes they could buy items of similar quality at lower prices from other places, but they are not allowed to do so. It appears the University might be making some profit by reselling items to the contractors. The contractors also feel that the University charges them excessive amounts for various services. For example they are asked to pay Rs.500 pm for deep freezer rent and maintenance, which would amount to Rs.6000 in a year, nearly equal to the actual cost of deep freezer. Thus, the cost of purchasing deep freezer, which remains in use for many years, is recovered in a year through rent and maintenance charges.

[10] These rules are stated in the

[11] This poster was put in the mess/canteens of the twelve hostels of

[12] Significantly, the theft took place on some other day and the charge of theft was based on allegation that the worker was found roaming in the corridor of the boy’s room. In fact, room service is very common in the boys’ hostels of

[13] There was a lot of confusion on the plan of the strike. The breakfast had already been served. The contractors tried to desist the workers and asked them to return to work. They were successful in weakening the strike but the workers of hostel-4 decided to continue with it. They refused to prepare the lunch and return until the warden intervenes, who was himself busy with the senate elections.

[14] Significantly, the very students who charged the worker for theft were among those who used to purchase cigarettes from him.

[15] The copies of the report were sent to all the members of the senate, including the Vice Chancellor, the Dean Students’ Welfare and all the Wardens. Besides this, the copy was also sent to the Chancellor of the University and the Labour Commissioner of

[16] The issue was raised by Rabindra Nath Sharma who drew the attention of the Vice Chancellor towards the pathetic conditions of hostel canteen and mess workers and said that neither minimum wages were being paid to them nor were the prescribed working hours observed (Panjab University Senate Proceedings, 20 March 2005, p.39) and was supported by G. C. Garg who added that ‘the conditions of the hostel workers should be improved and sheds be constructed for hostel workers because they were doing valuable service to the University’. (Ibid., p.40)

[17] The posters read; ‘More than 400 Mess/Canteen Workers are not being paid even half of their Minimum Wages. This is a serious infringement of their basic democratic/legal rights’; ‘Can anyone take care of a family with a meagre income of less than Rs.1500? Can anyone pay for health, education and shelter needs of ones children with this income? More than 400 mess/canteen workers in Panjab University are being denied basic wage-rights’; ‘University collects through the students Rs.10 pm and Rs.40 pa in the name of Mess/Canteen Servants Welfare Fund and Medical Aid of Mess/Canteen Servants. This money amounts to more than Five Lakh Rupees every year. Where does this money go?’; ‘Our Constitution says that

[18] The experience of

[19] Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan- Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu Domestic Workers Union, National Fishworkers Forum, National Campaign Committee of Rural Workers, Hind Mazdoor Sabha, Kashtkari Sanghathna, National Alliance of Agriculture Worker Unions, Dalit Social Forum, Self Employed Women’s Association, Campaign Committee for Legislation on Construction Workers, Kanch Udyog Krantikaari Mazdoor Sangh, Domestic Workers Organisation, Anganwadi Workers Union, etc.

[20] Report on the Working of Minimum Wages Act, 1948 (1998), p.i.

[21] Report on Evaluation Studies on Implementation of the Minimum Wages Act, 1948 in Bidi Making Establishments in Madhya Pradesh, (2001), p.i.

[22] Unorganised Sector Workers (Regulation of Employment, Conditions of Service, Social Security and Welfare) Bill 2004 (3rd draft) (2004), p.3.

[23] Ibid., p.4.

[24] It was recommended by a technical group on umbrella legislation for unorganised sector at a National Seminar on Unorganised Sector Labour: Social Protection, Skill Development and Legislative Intervention held on 7th November 2002 at Vigyan Bhawan and organized by V. V. Giri National Labour Institute, Noida, (Proceedings of the National Seminar on Unorganised Sector Labour: Social Protection, Skill Development and Legislative Intervention, p.2.)

[25] National Commission for Enterprises in Unorganised Sector was set up in September 2004 under the chairmanship of Amit Sengupta to examine the problems of the unorganised sector and propose means to overcome them.

[26] The national minimum social security cover creates an entitlement for all the registered workers in the country. It does not seek to replace the social security schemes which have been introduced for selected groups in a number of States. The national minimum social security cover will be a contributory one. Contributions to be made by workers, employers (wherever identifiable), and the Government shall be @ Rs.1 per day per worker (i.e. Rs.3 per worker per day or Rs.1,095 per year). Wherever the employer-employee relationship does not exist as in the case of the self-employed or where employers cannot be identified, or collection is too difficult, the Central Government and the State Governments will pay the employer’s contribution in the ratio of 3:1 respectively. The contribution of the Government will be divided between the Central and the State Governments in the ratio of 3:1, respectively. For workers belonging to BPL households, the contribution will be borne by the Central Government. The Commission has proposed the creation of a National Social Security Board, State Level Social Security Boards and Workers Facilitation Centres at the local level as decided by the State Boards. The State Board, consisting of representatives of all stakeholders at the state level, is the key implementing agency in the Draft Bill proposed by the Commission.

[27] Conditions of work and related aspects are the main concerns of wageworkers. As for self-employed workers, the Draft Bill has proposed various measures for the protection and promotion of livelihoods. These relate to the provision of credit, right to common property and natural resources, use of public space to engage in economic activities and the promotion of associations of self employed workers.

[28] To oversee the implementation of the provision of this Bill, a State Advisory Committee consisting of representatives of organisations of unorganised workers, ministries concerned and an appropriate number of experts have been proposed for every State.

[29] If the problems pertaining to the payment of minimum wages and other provisions to the unorganised sector worker were limited to the absence of legislation for them, it could have been sorted out by extending the provisions of Minimum Wages Act, 1948 to this sector. But the problem does not seem to lie with the existing legislations but with their enforcement. Thus when the

[30] Hirway points out ‘the bill covers non-permanent workers and subcontracted workers of organised factories and production units under the purview of the minimum package of social security. This is indeed very dangerous as subcontracted workers need to be treated as a part of the workers of the respective factories or production units. For example, sugar cane cutters who produce raw material and feed it to factories need to be considered as a part of the factory workers, as they work exclusively for their factories and participate in the production process of manufacturing sugar’ (Hirway (2005), p.380).

[31]

[32] The Unorganised Sector Workers Bill, 2004: A Critique (2004), p.2.